Categories

-

Archives

- April 2016

- February 2016

- October 2014

- March 2014

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- February 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- February 2011

- July 2010

- June 2010

- April 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- October 2009

- August 2009

- July 2009

- June 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- March 2009

- February 2009

- January 2009

- December 2008

- November 2008

- October 2008

- September 2008

Outlaws of Time Giveaways

On April 19, 2016, I am launching OUTLAWS OF TIME: THE LEGEND OF SAM MIRACLE. It’s my first novel in two years, and to commemorate the memmorateness of the occasion, I’m focusing all my book promotion on giveaways!

Anyone who buys OUTLAWS in the first week (no later than April 23) will receive their choice of rewards. Multiple copies earn multiple rewards. I don’t care what format you might purchase or which retailer you might use, just email a receipt to sam@outlawsoftime.com and name your reward.

Over the years, I have heard from thousands of aspiring writers, young and old. And so my first giveaway centers focuses on all of you with interest in the craft. Read the rest of this entry »

Hello Old Readers, I Have a New Book

Way back yonder, in 2005, I was sitting at a corner desk in my children’s play room, shoveling together the first piles of words and ideas that would eventually become the 100 Cupboards trilogy. Soon after giving that manuscript a break, Leepike Ridge came pouring out in a rush. Leepike was published in 2007, and 100 Cupboards a few months after (right before the New Year). Over the last decade, I have hopscotched my settings all around this country, trying to tap various unique facets of the marvelous whole I refer to as Mythic Americana. Leepike puts the treasure of an ancient Asian explorer in the new world. 100 Cupboards, Dandelion Fire, and The Chestnut King use Kansas (and a touch of Oz mythology) as a launching point. The Dragon’s Tooth, The Drowned Vault, and Empire of Bones do a bit more continental roaming, but Oconomowoc, Wisconsin and Lake Michigan serve as origin and hub. Boys of Blur wades through the Florida swamps and races old-world monsters through the thick muck of the sugar cane fields.

Ten years and eight novels took me all over the place, but I had never set my narrative feet firmly in the Southwest—one of the most striking regions on this continent. And my other stories hadn’t drawn much on two of the most distinctively American mythic genres—the western (tall tale), and the modern superhero story. The time had clearly come… Read the rest of this entry »

For All Your Signed Copy Needs

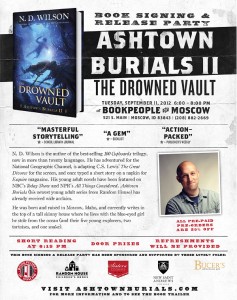

Want a signed copy (or seven) of Ashtown Burials II: THE DROWNED VAULT (or THE DRAGON”S TOOTH, or 100 CUPBOARDS, or…)? Of course you do. Well, my local independent bookseller has one (or seven) for you (and will ship). Call Bookpeople of Moscow at (208) 882-2669, place your order, and consider it done!

The Pitcher

At the behest of some among the nameless, I’ve decided to post a couple of old pieces from the era of my life when I was an eager aspirer, but had not the gumption (or the time) to attempt a novel. I focused on short stuff that I could manage and that could help me refine my word juggling. This one is from the summer of 2000, when I was picking up classes toward my MA at St. John’s in Annapolis, MD. I was 21 (pretty sure), and the root scenes for the piece were all real.

So here’s a little flashback to my beginnings. I have resisted the amazingly powerful urge to edit and improve…

The Pitcher

He was there the first time I made the drive. Just off the left side of the road by the light. Winding up and pitching. His motion was jerky and hard, too hard to be accurate. But then he couldn’t be more than four years old, and his hand was empty. As I sat at the light I watched the repetition of this exertion. He was off by himself in the grass of St. Paul’s Lutheran Church. There were other children dancing around and stomping, yelling, singing and falling down. But none of them even noticed the small, black pitcher off to the side, and he never took any notice of them. Then the light had changed.

The pitcher had been in my head all evening. As I sat and discussed Aristotle and Aquinas, his motion repeated itself again and again in my mind. The intensity of his contorted face as each strike blew by a batter, the rapid motion of his small dark arm as he followed through, almost over-balancing, his windup as he slowly stepped back before exploding forward bringing his empty hand around to deliver; all of these things played themselves out on the table in front of me. With a small motion of my fingers I joined in. My pen was swinging at every pitch, hitting nothing but air, strike out after strike out. Dust rose off the catcher’s glove behind me as each pitch hit its target. Class ended and I went home to eat, my defeat forgotten.

I drove to class four times a week. Four times a week I pulled up to a red light and looked left. Four times a week I watched a small, black boy pitch with his heart. He pitched in every scenario. He came from behind, he battled to the wire, and he strolled in victory. I watched him walk around the mound with pride in his step and such a grin on his face that I knew his opposition couldn’t be smiling. When he walked and laughed I couldn’t help but smile myself. The game was obviously in hand. But there were other games.

I had run out my door into the usual moist August heat of Maryland without a thought of the pitcher. The world was a grand place even in its humid glory. The wet, warm greens held hands with the dry, stark blues and a breeze blended them both. It wasn’t a long drive and I spent most of it looking around at the world. Then, I turned a corner. As was frequently the case, when I saw the light in the distance I remembered the pitcher. I knew that soon I would look over my shoulder and watch a child swing his empty hand. I would see a small boy off by himself, apart from the games of the others, dreaming. I knew that he would be standing where he always stood, where he could be by himself but still under the eyes of the tired woman from St. Paul’s Lutheran Church whose job it was to keep the children born of other women. I knew a pair of small eyes would be staring into nothing and that they would see a batter to defeat and the catcher’s target held waiting. He would focus his mind and body beyond the abilities of any of the great pitchers. He would throw with concentration that is unequaled, for he had no glove on his hand, no hat on his head, his fist held no ball, and while the traffic of Route 70 poured by he could climb the mound, remove reality, and swing his arm.

I didn’t look over until I had stopped at the light. And when I did he wasn’t pitching, he was circling the mound. By his look I knew he was in a battle. His face registered blank intensity as he walked. There was no pride in it. He strolled to the spot where I knew his eyes saw a dirt mound instead of green grass and assumed a position that obviously wasn’t a windup. He was in the stretch. There were runners on. He glanced right. Runner on third. He glanced left. Runner on first.

“He’s going.” I told the inside of my truck, and I could tell my pitcher knew. He glanced left again. The runner on first would steal. The pitch came, batter takes the strike. Runner on third dances, daring the catcher to throw to second. Runner on first advances. The ball is back on the mound. I glance up at the light. The red glow still hangs in the air, and traffic still streams past.

The pitcher is back in the windup. Runners on third and second. By his face I know we are in the ninth, hopefully the top, but because of the obvious pressure on the pitcher’s face I doubt it. My pitcher’s small body stands on the mound gazing at the catcher. He takes a sign and I know it’s a fastball.

“Bunt.” I whispered. The windup comes, the explosion in the small arm. The light turns but not before I see the surprise on the pitcher’s face. He spins around looking up. He shakes off the glove that only he and I can see and puts his hands to his head and stares out to the wall, waiting. The batter took it for a ride. He parked it. Homerun, three runs score. My pitcher falls to the ground in shock. I turn with the traffic and the image is growing smaller in my mirror. A small body in the green grass, the other children don’t even look over, but there is a tired woman walking towards it.

After that, I couldn’t look at him the same way. The next day he was smiling and strutting again, but even his enjoyment seemed different to me. I could still laugh when he did, but the joy was double edged. He was surrounded by traffic, given by his parents to be cared for by another; he had no ball and no batter, and still he enjoyed himself.

I would have bought him a ball, but I knew he wouldn’t be allowed to throw it. The one time something had risen in his hand it had been a pine cone, and the tired woman had removed it before a single pitch had been completed. I would have stopped and played with him but I knew people didn’t take kindly to strangers approaching day care centers. I would have done a lot of things, but I did none of them. Instead I always went to class and watched him pitch from there, the same way he watched a batter crowd the plate.

Then came the last day. There were many distractions to keep me from remembering my pitcher, but for some reason he still climbed into my head. Everything about him flooded my brain as I loaded my book bag. His bib overalls, his oversized tennis shoes, his uncut hair, all these things presented themselves and I did not realize why until I was leaving. It was the last day I would ever see him. It was the last game of the season. I would drive by, watch him throw his arm, and drive on. Only this time driving on was permanent. I would never make the drive again. I flew home the next morning. I realized that he was a boy that I had always wanted to talk to; I wanted to know his name and his mind; I wanted to see his life. But I was driving by.

The drive felt longer than it usually did and I spent the time oddly not thinking about class, or the past session, but about that thin boy with an empty hand. I wondered about his father, and if he had played baseball. I wondered if he had simply seen it on TV and latched onto it. His behavior was detailed enough in its imitation that he had to have watched a good deal of baseball. I thought about his drive. His desire to pitch as hard as he could when he wasn’t throwing anything to anybody and knew it. But I knew he went home tired every night. Tired from the workout of throwing his arm. Where did his love of the game come from? Where was his father? Who would play catch with him? We were all too busy. We were driving by. His father and mother were driving by. I was driving by. A thousand others were driving by. Only the tired woman wasn’t driving by, and she was busy, busy sitting and making sure my pitcher didn’t really throw anything. He was as invisible as his catcher, and the batters he struck out. Humanity’s traffic sped by him and had stored him safely on a piece of grass that he had made a mound. All things were blind to him, and he returned the favor.

I reached his street and looked at the light hanging in the distance. It was green. It was never green. It would change. I kept driving and watching the light. It wasn’t changing, I began to feel nervous, I needed to say goodbye to the pitcher. I looked for a place to pull over and there was nothing. I was in the left lane with traffic on my right and oncoming. I was through the light, and I had only time to glance over my shoulder as I turned.

The pitcher was standing on his mound staring into nowhere. He wasn’t pitching. Was he taking a sign? I couldn’t tell. I grabbed my mirror and saw the beginning of a windup before he disappeared.

The next semester I had moved and didn’t need to make that drive anymore. But I did. I drove by before class. The grass was empty of everything. There were no children laughing and screaming and falling down. There was no tired woman. There was no pitcher. I drove to class. I sat at the table. Someone was talking about Homer. I looked down. My pen was swinging.